Winter on the Intracoastal: Creeks & Rivers

In mid-February, every time someone asked where we were from and we said Seattle, the topic of the Superbowl came up again. “That was a weird game,” people said. “It seemed as if the Broncos did everything in their power to lose.”

And that’s a great lead in to the way this next leg of our trip went. It seemed as if we did everything in our power to fail at cruising.

Hurry Up and Wait

Leaving Beaufort, our route south wound between gorgeous sandy islands and through turquoise water. I’ve neglected to mention that about Beaufort – the water there is blue green rather than the tannic tea, root beer, and strong coffee colors it had been since we entered the Dismal Swamp.

Our goal for the day was Mile Hammock Bay, 40 miles from Beaufort. But first we had to stop for fuel. And there’s where things started to go wrong. We waited at the dock for 45 minutes for the owner to come from “just ten minutes away.” Then we tried to stop for stove fuel at a harbor that, according to the cruising guides, was just blocks from a major hardware store. More on the accuracy of cruising guides later.

Back underway just after lunchtime, we got a boost from the current, which pushed us along at 7 to 8 knots. The jib helped some of the time. Other times it hung slack.

I’d read in the guide that there was a shoaling problem at green marker 61a near Camp Lejeune. When we got there however, several buoys had been added, confusing what was shown in the guide and on the charts. Watching Navionics, our most up to date source of information, I suggested Tom keep to the center of the channel. Luckily he slowed way down, because my advice was bad and we found that shoal. He quickly spun Sunshine toward the new green marker and got back into deeper water, just barely keeping us from sticking there in the middle to wait for higher tide. Now gun-shy, we proceeded at reduced speed, through the firing range of Camp Lejeune. Yes, Virginia, they shoot right across the ICW. Blown up tanks and bunkers line the eastern bank. Meanwhile, the light was getting noticeably lower in the sky.

The Onslow Beach bridge came into view just before 4 PM. We couldn’t make the 4:00 opening, and at the speed we were going, didn’t think we could be there in time to ask for a 4:30 opening either. We figured we’d have to idle in the current until the 5:00 opening. With sundown at 5:45 and the anchorage an hour away … we’d be finding our way in the dark.

It can be a little annoying to have to live by an arbitrary schedule, but bridges rule on the ICW. In the 40 minutes we had the bridge in sight before it opened for us we saw three cars drive across. And once it did start to open, the process took at least 15 minutes. If we’d known that we could have been there in time for the 4:30. Note to self: always open a dialogue with bridge tenders well in advance of arrival.

We arrived at the anchorage at dusk and found a brightly lit ship at the dock. I’d read (in those questionable cruising guides) that sometimes the anchorage is closed for military maneuvers. There’s not much else around, so we could only proceed and hope for the best.

Perhaps it was angst, but I nearly blew the anchoring by backing Sunshine too fast before Tom had secured the anchor line to the cleat. He shouted at me to slow down and had to hold on until the boat stopped. He-Man stuff. This could have ended very badly, with him injuring a hand. I kicked myself for not being more diligent about improving my boat handling skills. I had been letting him do most things because he’s stronger and can do them quicker. It’s a bad habit, and I vowed to break it by putting in the practice time.

Conditions, Unless Otherwise Noted, Should Be Considered Damp. – Christopher Moore, Fool

After a peaceful night, we woke to light fog. It didn’t look too bad, so we carefully motored out of the bay – and promptly came back in. We could see far enough to get out of the anchorage channel, but then the main channel markers were nowhere to be found.

Fog kept us there for two days. Tom fixed a troublesome light, removed old velcro from the end of the starboard settee and replaced a corroded screw in the head. I caught up on writing tasks and wiped away endless condensation.

I asked Tom if he’d looked at the weather report and he said, “there is a chance of claam-my” in the voice of the National Weather Service weather bot, who says “cloww-dy.”

The Lure of the Outside

Having run aground once, we both started to think about taking the outside route down the coast. I’d read about all the shoaling ahead, dredging programs halted due to budget cuts, bridges that open infrequently and how hard it is to stay in the channel. The ocean was starting to look like the less high maintenance option.

Then I remembered a favorite book, The Control of Nature by John McPhee. And there was a little lesson in patience. Just days into this adventure, we’d already begun to look at shoaling as a problem. Fix it for us Corps of Engineers! But it’s just nature, taking her course. We’d always believed that humans had to find ways to live with nature rather than trying to change it. So now it was time to embrace the challenge.

That evening I felt hot and sticky, went outside for fresh air and found an absolutely gorgeous evening. Fog still lay at the foot of each island, cloud banks at the west and east sides were outlined in sunset pink. Frogs were at it in the marshes and unfamiliar birds, including one that buzzed, called and responded across the still water.

My Turn to Keep Us Grounded

With a clear, beautiful, windless morning, we set out to negotiate the shoals of New River Inlet. The ICW takes a big bend there around several islands, and the river is depositing sand against the eastern bank. At one point I came upon a red marker that seemed to be in an unusual place. The bottom was getting closer to our keel and I remembered reading in the cruising guide that the markers switched sides somewhere, but didn’t remember exactly where. Tom was below, so I throttled back knowing he’d come up to see what was going on. He checked charts and helped me decide where to go. We got through, but I saw the depth go to 3′ 8″, so I plowed though some very soft mud.

Mind freewheeling as I drove, I decided that the floats of crab pots lining the western edge of the channel might be a good secondary indicator of safe depths. Later that night my deduction was corroborated by a very helpful article on Windcheck called “10 rules for the ICW.” One rule was: “The crab pots are your first indicator of where the edge of the channel is. All else will vary and conflict but the crab pots are always placed along the edge.”

We negotiated two bridges smoothly, then after I hailed the Wrightsville Beach bridge and arranged an opening, the tender called back and said to come ahead fast, he would open early for us. But when we arrived and were anxiously watching for the red and white striped arms to come down and block traffic, the tender called back to say oops, he wasn’t going to be able to do it early after all. Tom had to stop, reverse, and battle the current again.

We anchored and went to check out this ocean front resort town. We hadn’t seen the open ocean since New Jersey, six weeks earlier. This southern shore was a little different. Grinning like fools we walked in bare feet among surfers, palm trees and pelicans. Two long piers jutted out into the water, giving us a bird’s eye view of Frying Pan Shoals and passing dolphins. Historic cottages were sprinkled among overwhelming highrises. Beachwear and surf shops mixed with bars, burger joints and taco stands, most closed for the season. A friendly, though expensive and funkily stocked, grocery store served as the retail hub of the winter neighborhood.

Making Drama Out of Good Intentions

On our way out of Wrightsville the next morning we decided to tie up at the marina closest to the bridge and hike the mile or so to the grocery and hardware stores for food and propane.

Before pulling up the anchor, I reminded Tom to check the raw water intake. We’d run through those shoals and there might be some sand or debris in the filter.

He shut the raw water sea cock, cleaned some weeds from the filter and started up the engine. We pulled up anchor, motored to the dock, hiked to the stores, did our shopping, came back and cast off, heading on down the channel. I went below to put away groceries and something sounded wrong. I took me a moment, then I ran up on deck shouting, “Did you re-open the raw water?”

The answer is obvious. We dropped anchor in the channel, shut off the engine and Tom started working on the problem while I monitored our position. He called Jason (our beloved, lifesaving, friend and mechanic) for advice. Long story short, we had to return to Wrightsville Beach to buy a new impeller, a small rubber gear that pushes water through the water pump.

With the new one installed, Tom heard air escaping somewhere in the system. He searched and found a small hole in our Vetus waterlock muffler. Those things are costly, and being the handy guy he is, he decided to try to patch the hole. He cut a chunk of plastic off the muffler’s unused mounting bracket for patch material and, using a soldering iron, added drops of plastic to the edges of the hole, making it smaller and smaller until it disappeared. Once reinstalled, the noise was gone, the temperature remained cool and all was well with the engine. But the day was shot, so we anchored at Wrightsville again, took a long walk on the beach, went to the end of the pier to watch dolphins cruise by, then headed home for sun-downers in the cockpit.

Making Calabash Creek the next evening, we sneaked ashore and took pictures of roosting pelicans and found pelican bones. That was cool. We slept well in the quiet anchorage then, getting out of bed in the morning, I tweaked my back. Not so cool.

Are Cruisers Stupid?

The cruising guidebooks contain a lot of warnings about scary, dangerous things. Over and over they say things like “Give the green marker a wide berth.” They really could have said it just once, it’s basic common sense to give all markers a wide berth unless advised otherwise. Most of their warnings are for things that turn out to be nothing. By this time I’d just started to tell Tom – “the cruising guide says ‘booga-booga-booga’ about this next section.” And that was true of most sections of the ICW.

Now we were coming to the fearsome ROCKPILE, the biggest “booga-booga-booga” of the whole trip. Stories of bent propellers and broken hulls abounded in the guides and on the web. With my hurt back, I could hardly move to help if we got into difficulties. So naturally, I was apprehensive.

We were alone during our transit, a perk of winter boating, and could enjoy the Rockpile, which turned out to be gorgeous. At low tide the rock outcroppings are lacy landings lining the banks, some topped with small bonsai style gardens.

In the end we decided the Rockpile only scares boaters because they’ve been sailing between banks of pluff mud for weeks or months and have forgotten that banging into some shores can hurt. I assume most collisions and damage happen during the high season when the ICW is crowded. As in most disasters, overpopulation is the real problem, not the landscape.

Bartlett’s Familiar Laws of Boating

At Enterprise Landing, we nestled behind a cypress island in an oxbow. Stuck on board with my injured back, I removed my cell phone from its waterproof case to take a picture of Tom rowing through the swamp between cypresses lit by afternoon sun. There was a bloop, and suddenly I was holding only the back of my phone. The front had dislodged when I pressed the camera icon, bounced on the side deck and fell overboard.

We’re developing Bartlett’s Familiar Laws of Boating. The first two tenets are:

– If it can tangle, it will tangle

– If it’s not tied on, it will fall overboard

The river was muddy, the current swift and Sunshine was swinging at anchor. There was no way to tell where the phone landed. I’d threatened to jettison that Aggravating Android a million times, but I swear this was an accident, or karma, for being dumb enough to take it from its case. Add finding a replacement to the to-do list for our next stop – Georgetown, SC.

We had an easy day drifting slack-jibbed down the Waccamaw River, where the biggest challenge was a constant drizzle. Then, a mile from Georgetown, simultaneously the wind slammed us and the engine sputtered. We were low on fuel. While I sailed on down the channel past Georgetown, Tom got out the extra jug of diesel and poured it into the tank. The motor wouldn’t restart. So once again Jason, our best speed-dial buddy, helped Tom get it going. By that time we were three miles past our destination and had to buck a major headwind back up river.

Sheep, Wolf and Bale of Hay

At Georgetown we got hit with another winter storm. Ice coated everything, again. Up and down the creek we could hear trees breaking under the weight. When the storm let up I needed to do laundry. My back was still not feeling great, but I had Tom row me to shore, and while the clothes were in the marina’s washer, I took a therapeutic walk through a southern winter wonderland. Georgetown’s palm trees and moss draped oaks were entirely encased in ice. Wanting to take pictures of the phenomenon, I pawed through my bag for my phone … yeah.

With only one phone, going ashore became a version of that old puzzle about how to get three things that will eat each other across a river. In general, we like the dinghy to stay with the boat so the person aboard isn’t stranded. But when the winter wind is blowing and hatches and ports are firmly shut, how does the person ashore let the person aboard know they’re ready to be picked up if there’s only one phone? Planning a time to meet always left one of us sitting in the cold. I stood on the ends of docks and shouted to no avail. We tried using email. But both parties have to have internet access. At one point I posted to Facebook: “Tom Bartlett, check your email.” How on earth did sailors manage this in the days before cell phones and social media?

Things Get Better Before They Get Worse

A few days later, the world thawed out and we were able to head on down the Cape Fear River. We anchored across the ICW from McClellanville in Five Fathom Creek. The weather was warm, I was feeling good and there were oysters lining the shoreline. Unlike the Northwest varieties, which lie sedately across the sand, here they grow standing up, their shells creating treelike formations that seem to reach for the sun. Inside are succulent, sweet morsels no bigger than your thumb, with only a hint of sea salt. Yum. Quiet, remote marsh anchorages like this were fast becoming our favorite places.

Next stop, Charleston. I’d long been looking forward to seeing this bastion of antebellum history. To touring Fort Sumter and hearing about blockade runners. In the end though, Charleston turned out to be less about past excitement and more about current events.

After crossing Charleston Harbor at the worst possible time – wind against current, water very rough, we headed for the main anchorage in the Ashley River across from City Marina. I’d read on Active Captain about people losing their anchors here due to snagging debris on the fouled bottom. And the eclectic collection of vessels anchored there did point to potential problems. So I insisted – yes insisted – that before Tom let our precious Rocna down, he had to rig a trip line.

We’d been planning to start using one of these for some time. It’s basically a rope just long enough for high tide. One end is tied to the anchor, the other to a marker buoy so that, should the worst happen, you always know where your anchor is. It also helps in loosening an anchor that’s stuck under something. Tom didn’t want to take the time to dig out all the parts right then, but If we were ever going to use one, this was the place to do it. I’ve been patting myself on the back for sticking to that particular gun ever since.

The current runs swiftly through the Ashley, and once again, Sunshine danced around her anchor at the change of the tide. If the wind and tide were opposed, she wrapped the anchor line along her keel and couldn’t turn bow into the current. We made it through the first night by letting out scope to free her. Then, in the morning, the weather was calm and we headed ashore to check out the town, which was on our list of possible places to stay a while.

Charleston – moss draped oaks, old houses with front doors that open to verandahs instead of foyers, buried ruins, fortifications, pecan pralines, a big ole pineapple fountain, miles of walkable waterfront parks. The one thing we hoped for that we didn’t find was a hole in the wall local restaurant where we could try the regional cuisine. We finally had barbecue at Sticky Fingers, which was good, but more touristy than we like.

Things Get Worse Before They Get Better

Around three in the afternoon the wind began to blow and I tried hard not to worry about Sunshine. As the sun was setting we headed the dinghy across the river and something didn’t look right. Our boat was in the wrong place. Had the Rocna dragged? Inconceivable. When we got closer we saw she was tied to a mooring. And back where she should have been, there was the trip line float, marking the location of our anchor. The anchor line hung slack from Sunshine’s bow, a frayed end about 20 feet from the cleat.

Having no idea what had happened, separated from our anchor, and with no light, we had little choice but to remain on the mooring for the night. It’s hard to trust an unknown mooring though. What’s down there? Is the anchor on the bottom big enough to hold? Are the line and chain in good condition? I woke with every sound.

The next morning a fellow who camped out occasionally on a nearby boat paddled over in his inflatable kayak to explain what had happened. Daniel had seen Sunshine drifting close to shore, so he paddled down the river to get help from Kyle, another liveaboard who had a dinghy with a motor. Together with Lewis, a third local, they managed to pull Sunshine off the beach and tow her to the mooring.

Though we still didn’t know what caused her to break free, we now did know how valuable the homeless community (of which we often feel part) can be. We were very lucky that Daniel was observant and Kyle and Lewis were available and willing to take action. Once we’d retrieved the anchor, we bought them all thank you gifts and got to know them pretty well.

After the friendliness of the anchorage, we found the Charleston waterfront proper to be relatively unfriendly to boaters. All the marinas cluster around the bridges over the Ashley River, the traffic noise is intense. City Marina’s Mega Dock is a mile long, geared to mega yachts, very expensive and far from everything. The marina district doesn’t connect to any parks, trails or buses. There are no docks along the city waterfront for anything but tour boats. We walked the whole waterfront and found only one other small marina where boaters can tie up. It too was remote. After a few days we began to feel that this was not our place.

The morning we were leaving, I popped my head out of the hatch and saw that one of the more creative floating homes was loose and headed toward the ICW. Ai yi yi – it was time for our karmic payback. We hopped in the dinghy and went to see what we could do. Lewis, one of the fellows who had rescued Sunshine, was there checking things out too. The boat had broken both its anchor chains. It had no engine and no rudder. The tide was going out and the wind was blowing hard in the same direction. So towing the boat back up stream with our little inflatable was tough. We tried to get the boat to the same mooring we’d been on, but the wind and current stopped us. We ended up rafting the it to another and dropping our spare anchor to help secure them both.

We watched anxiously for any sign of dragging until the owner arrived, along with Kyle, with his bigger dinghy and motor. The guys worked to secure the boat on a more substantial anchor. But by that time it was noon, so we stayed one more night. As soon as there was light enough we got the hell out of town.

This leg of the trip wound through narrow cuts and twisty rivers, all of which are very shallow and need to be transited on a rising tide. The tides that week were extremely high, good for us. We could get through as far as the mouth of the Dawho River, then we’d have to anchor and wait for the next day’s high to make it down the Dawho. We chose Steamboat Creek as our final stop for the day and we’ve never been happier with a choice of anchorage. It was beautiful, serene, the banks were lined with the best oysters we’d ever eaten and at night the stars showed bright because there was no light pollution from any town.

Down the Dawho and through all the cuts we went, current with us, winds gentle, tide nice and high. And then we started the run up the Coosaw River, which would take us to Beaufort, (beeyou furt) SC where we would stay for one night. The tide turned and began to flow out, the jib hung slack and the day got warmer and warmer. Battling the current, we were making only 3.5 knots and the engine began to heat up. We slowed down to 3 knots and monitored the temperature. When we got to Beaufort we’d have to run a flush of the heat exchanger, which Jason had recommended.

At the Beaufort Downtown Marina, we tied up at the fuel dock to fill up on diesel and water and check the engine. However, we’d neglected to call ahead, so the attendant kicked us off in favor of a big power boat that apparently needed all 500 feet of dock in order to maneuver. First time we’d encountered this requirement to notify a marina ahead of time that we wanted to come give them money.

Whatever, fueling could wait for later, so we headed for the public dock instead, where we could tie up while we explored the town and had dinner and showers. Between two small powerboats was a spot just big enough for Sunshine. The current was swift and a strong wind was pushing us in sideways toward the dock. I thought we should ask one of the boats to move forward, but Tom decided to give it a shot and see if he could make it. He did, it was brilliant boat handling. I stepped to the dock quite elegantly, secured the lines without a glitch. We looked like pros.

The free dock is not a place to tie up for the night though. After dinner we headed out into the anchorage in the dark. This time we didn’t look so hot. We couldn’t go forward because the current would push us too close to the boats at the marina. Tom had to back out against the current while I stood on the bow just in case the maneuver didn’t work and we had to fend off.

In the morning, we moved across the river to the more protected Factory Creek anchorage to go to the nearby hardware store and clean out the heat exchanger. With less current and wind exposure we were much more comfortable. Unfortunately, by the time we had all the parts in place for the job, Tom started to get sick and a storm was moving in.

Public Docks Are Social Media

Rowing back and forth to the dock, in the rain, with bags of laundry and provisions, I met first Orion Scott, a former cruiser who provided local information and gave us a ride to Lowe’s for one last tool, then Iain and Jan Robertson who had anchored their boat, Jock’s Lodge near us.

The next day, with Tom down with the flu, I called Lady’s Island Marina to see if I could get a day pass to do laundry and take a shower. Steve, the manager, said come on down so I rowed ashore again and hauled another load and my shower bag down the street. When my clothes were finished it was pouring, and Steve actually offered me a ride back to the dock. Then, taking pity on me, he invited us to tie up at the marina’s t-dock for the night as a storm was coming and with Tom so sick we were going to be pretty uncomfortable. We took him up on the offer and when we arrived at the dock I think I heard him humming Hotel California.

The next night I had dinner with Iain and Jan at the Fillin’ Station, a local wonder of a dive bar where on Friday nights you can get a huge steak dinner for $10. After cruising for nine years my new friends were on their final voyage, headed back to the land life in Canada. They gave me surgical kits, a first aid book and Florida charts that they no longer needed, along with a wealth of cruising wisdom.

After the weather broke and the Robertson’s sailed away, Tom felt better and took a tour of Lady’s Island Marina. When he saw the shop he realized we’d stumbled on the place we’d been looking for. It had everything we needed – a quiet, protected location in a lovely marsh, moss draped oaks, access to supplies and materials, space to work on projects, a place to keep the van, friendly people and a dive bar just steps from our transom. So we settled in and Tom started making plans to fly north to retrieve the van and the rest of our belongings.

Google mapping his driving route from Rhode Island to South Carolina he learned that the trip takes roughly 14 hours.

It had taken us two and a half months by boat.

That Wraps the Winter Escape from New England Via the Intracoastal Waterway

But one last note before I close this saga. A couple of weeks after we settled in Beaufort, we had a diver install a new zinc anode on our propeller shaft. While he was down there he noted that there are two gouges rubbed in the back edge of our keel.

We surmise that while we were ashore enjoying Charleston barbecue, the tide changed and Sunshine began her customary dance around her anchor. Without us there to free the line, it chafed against the keel long enough to cut right through.

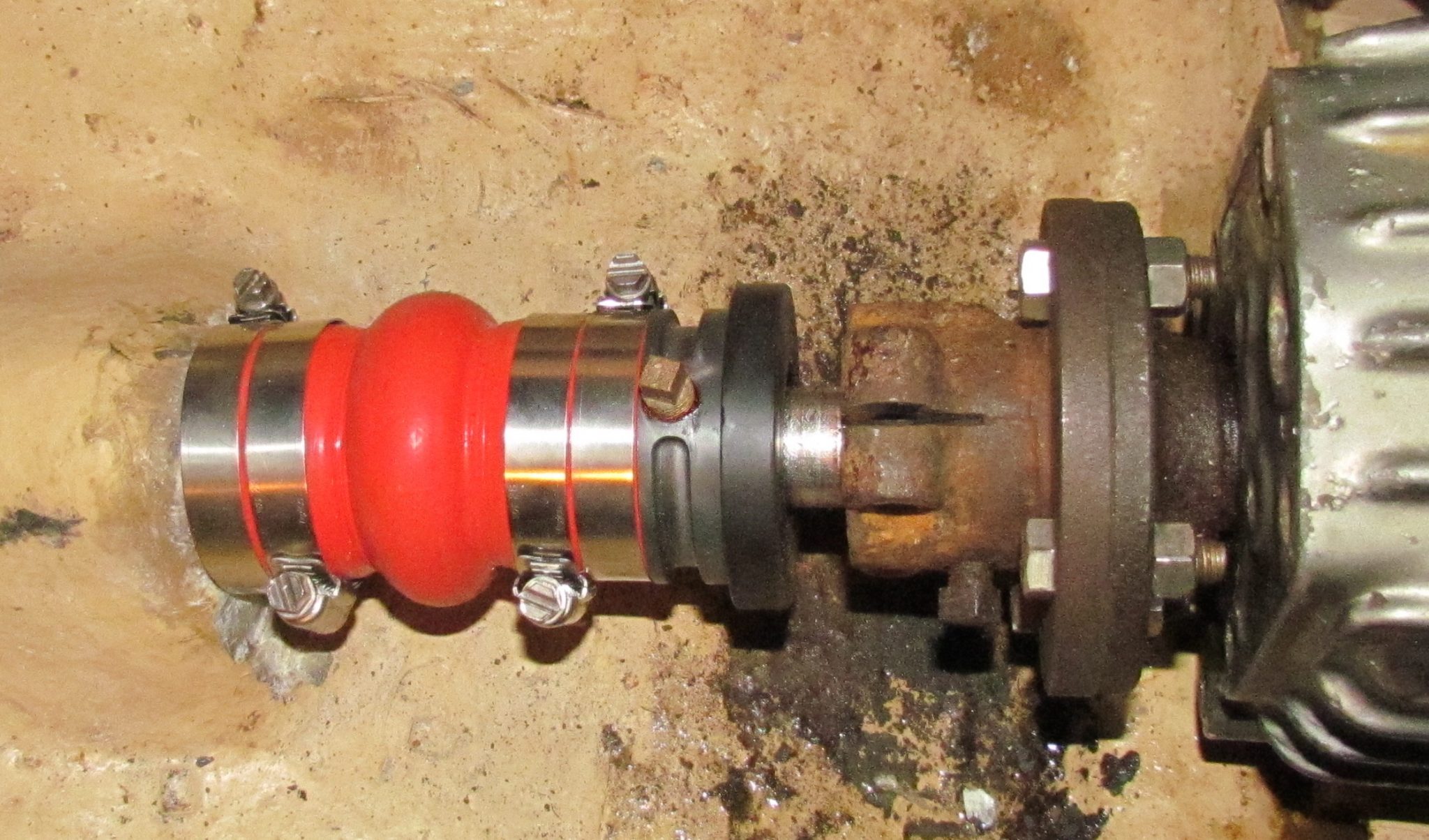

We’d already installed a stouter line and stuck closer to Sunshine when those conditions occurred. But those aren’t the final solution. Friends have given us ideas for curing the problem, we’ll try those when we finish our projects and head further south. For the moment though, we’re enjoying South Carolina life.

Read previous posts about the Escape from New England

Narragansett Bay

Long Island Sound

Christmas Cruise: Point Judith to Westbrook

Christmas Cruise: Westbrook to Stamford

Christmas Cruise: Stamford to Mamaroneck

Christmas Cruise: Mamaroneck, NY to Jersey City, NJ

New Jersey Coast

Christmas Cruise: Jersey City to Manasquan

Chutes and Ladders in Atlantic City

Red Nun 2CM I think I love you

The ICW

Fabulous travel log Nancy. I’m following with Google maps every anchorage along the way.

Thanks Bob, it’s great to have you along. By the way, I hope you noticed the comment bait I left for you and Candace … the part about how did cruisers contact one another before cellphones and Facebook. If you’d like the complete list of our stops, I think I left out one, Prentice Creek in Virgina. It’s just south of Potomac River. We got there so late and left so early that nothing happened there but sleep. it’s a nice spot though, from what little we saw.

Sorry I dropped the ball on Neanderthal Networking! We used ham radio for communication – setting up a set time and frequency for contact. We also used the Pacific Maritime Net pretty regularly. Also – we used a sextant for navigation – at least on one leg.

I certainly related to the problem of chain grinding against the keel, especially with wind against the tide anchoring situations. No fun!

But – it sounds like you’re really enjoying the trip, warts and all.